Medgar Evers, presente

Remembering a martyr in the Black Freedom Struggle who fought to unshackle Mississippi from plantation domination and observing his contribution to a 'Blues Epistemology' for liberation

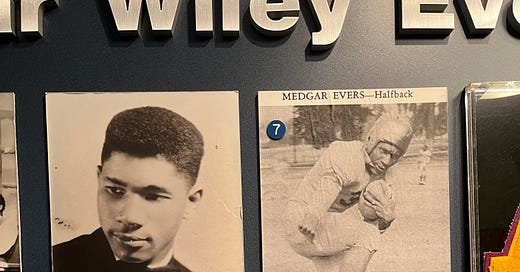

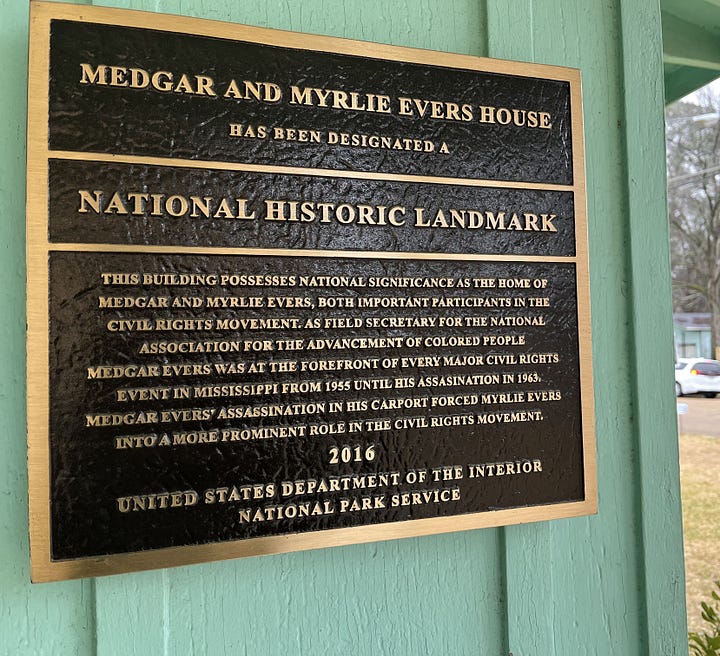

62 years to this day, on June 12, 1963, after attending an evening mass meeting, Medgar Evers was assassinated in the carport outside of his house in Jackson (Eversville), MS — shot in the back by a member of the white supremacist Greenwood Citizen’s Council. Brother Medgar left behind a wife, three children, and the legacy of a freedom fighter committed to his people and his land. His murderer was not convicted until 1994.

“I would rather die on my feet than live on my knees”

I visited the Medgar and Myrlie Evers House over two years ago as part of the 2023 MIT Civil Rights Immersion Trip, which I helped to lead. Immediately upon stepping foot outside the house, I felt something rising in my body and spirit. Standing in the carport where Medgar was murdered, meeting his daughter, hearing stories of Medgar as husband and father and community figure (like Medgar playing the piano for the family after dinner), seeing the bullet holes still in the walls and appliances, and learning from the dedicated staff caring for the home and the Evers’ legacy was one of the most impactful and overwhelming experiences of my life. It is difficult to describe the mixture of admiration rage, sorrow, and dedication to fighting this generational struggle that this visit inspired in me.

After our tour and conversation, some of us sat in our minivan for damn near an hour reflecting on the legacy, the impact, the words of Medgar Evers. We lingered on the reflections of his people and how they made so clear that he was a man of intense love and care for all of our people. I was then, and remain now, humbled by the conviction that it must of took for him to serve as NAACP Field Secretary for 7 years in the heart of one of the vicious regimes of social control, economic exploitation, political subjugation, and violent terrorism that was (and in certain ways still is) Mississippi — where my maternal family hails from as well. I still get chills thinking about that February day in Jackson, and about the turning point that it has become for me in terms of my own discipline, dedication, and duty to my people. Above all, walking away from the house that day, I understood how love — of family, land, community, life, struggle — could inspire someone to give all they had for the hope of liberation.

“Freedom has never been free... I love my children and I love my wife with all my heart. And I would die, die gladly, if that would make a better life for them”

For me, honoring our ancestor Medgar Evers is not only important to remembering the legacy of our Black/African freedom fighters or strengthening our ‘rootedness’ in grassroots struggle, but also to understanding his work as a legacy of intervening in processes of ‘planning and development’ designed to dominate and subjugate Black/African people and the working classes of Mississippi, the South, this country, and the world. As the late Clyde Woods wrote in Development Arrested: The Blues and Plantation Power in the Mississippi Delta, the white supremacist, capitalist planter bloc of the Mississippi Delta utilized the tools of regional planning, economic development, and political capture to repeatedly establish and re-establish total social-political-economic control over Black/African people and communities within their region, state, and even nation.

This ‘plantation power’ has taken many forms, but throughout history, “innovations” in regional planning and development have allowed the planter bloc to remain atop the ruling class throughout Mississippi and to spread the white supremacist, capitalist, patriarchal, imperialist ideology of the plantation not only throughout the United States, but throughout the world. These brutal methods have included the genocide of Indigenous peoples and giving of their land to white planters or ‘pioneers’, enslavement and trading of Africans, destruction of ecological, re-enslavement through labor capture and debt peonage and convict leasing, ethnic cleansing after Black/African labor became ‘surplus’, and weaponization of state and federal policy and funding schemes to economically undermine Black/African and working class people and power. To name a few.

The tireless work of Medgar Evers, as well as his contemporaries and those that followed afterwards, was not simply a struggle for the right to vote, but a struggle for an alternative mode of development and society — based in human dignity, self-determination, and total emancipation. As Woods would describe1, Medgar Evers was organizer and freedom fighter in the Blues tradition that emerged from the needs and expression of everyday Black/African people who attempted to explain and reorganize the structures and relations of domination that they faced. Evers — murdered earlier than Malcolm or Martin or Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner — unfortunately did not see the most of the fruits of his labor and sacrifice, but nor did he experience the betrayal of elements of his life’s work both by white liberals and the Black elites. Brother Medgar, like Fannie Lou Hamer, understood his struggle to be one for all Black/African peoples, which meant fighting for and with the poor and working class Black folks of Mississippi and the entire South.

This is fundamental to understanding what Woods’ sees in Brother Medgar’s ideology and work in the Black Freedom Struggle as an expression of the ‘Blues epistemology’ that is political, ethical, economic, cultural, place-based, and grassroots. This way of attempting to remake our places and our world emanates not from a identity reductionist understanding of what it means to be “Black”, but from the material, cultural, spiritual, and creative conditions and expressions of the poor and working class Mississippi Black folks, whose ‘structural location’2 in this country has forced them to develop a form of resistance and social understanding that can truly oppose the domination of ‘plantation power’ and its current imperialist manifestations. Brother Medgar expressed this alternative vision by committing his life to (re)constructing a future where Black/Africans in Mississippi in the United States could follow our own path of development and social construction, free from the vicious hold of the (neo)plantation, the planter bloc, and their white supremacist acolytes. And he understood that in order for this to be true, that system needed to be undone. Understanding that we can only achieve our freedom, our true liberation, via an ethic, analysis, and practice that uproots the historic and current forms of violent domination, and replaces them with a new world, an alternative born from our people, our cultures, and our commitment to liberation.

Recommitting to struggling for that new world, and refusing to compromise our people’s dignity and self-determination, is how I would like to honor Medgar Evers today.

“You can kill a man, but you can’t kill an idea”

We honor the courage and sacrifice of brother Medgar, of his family, and of the many many Black/African people in Mississippi, the African continent, and all places between and beyond who have paid the ultimate price for daring to fight for all of our freedom.

Rest in power, Medgar Evers.

“I think it appropriate at this time that I make a confession to you before we go any further, and that is that I love the land of my birth. I do not mean just America as a country, but Mississippi, the state in which I was born. The things that I say here tonight will be said to you in hopes of the future when it will not be the case in Mississippi and America, when we will not have to hang our heads in shame or hold our breath when the name Mississippi is mentioned, fearing the worst. But instead, we will be anticipating the best.”

Note: In under three weeks, we will further celebrate the lives and legacies of Medgar Evers, as well as Patrice Lumumba, on the occasion of their joint Centennial (both were born July 2, 1925).

I’m currently reading Development Arrested, so more to come about the book as a whole soon

Referencing Dr. Charisse Burden Stelly’s excellent analysis of the Structural Location of Blackness from Black Scare/Red Scare: Theorizing Capitalist Racism in the United States, which she also explains in an interview here on Millennials Are Killing Capitalism Live! and in a shorter form in this blog post:

“Blackness is a “structural location” peculiar to the intersection of capitalist exploitation and anti-Black racialization. Here, Blackness is something that exceeds the category of race, that is not reducible to class, and that does not fit the specifications of caste. [1] Born out of racial slavery, Blackness describes an economic relationship that also denotes an inferiorized condition, a disempowered status, and a subordinated emplacement in society. Blackness is value minus worth. Through an array of political economic functions—including accumulation, disaccumulation, exchange, use value, and the absorption of capital risk—Blackness exists as a capacious category of surplus value extraction. At the same time, Blackness is also the quintessential condition of disposability, expendability, and abject precarity..”